What’s the one book to read on leadership?

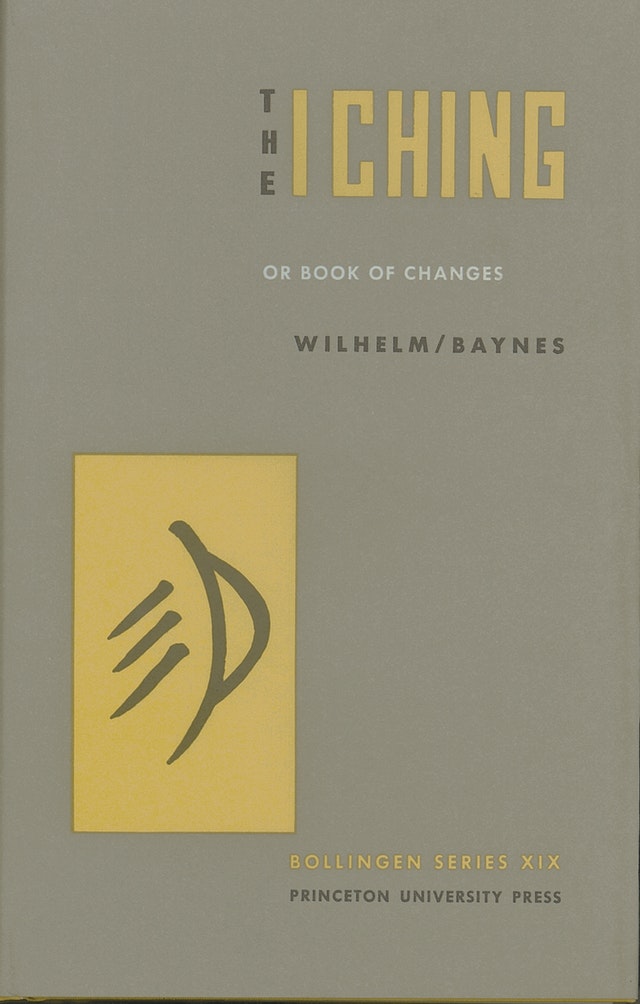

After decades of engagement with this topic, I return to a book my sister gave me in 1974: the I Ching, also known as The Book of Changes. It may be the single most useful book for leaders who authentically want to become good at what they do. (Be sure to buy the Princeton edition pictured above.)

Created in ancient China and associated with the teachings of Confucius, the I Ching may strike some 21st century Westerners as strange. There’s talk of elemental forces such as Thunder, Mountain, and Wind, for instance, and references to the social customs and artifacts of a far-away land in a distant age. But the messages are timeless. For example: When the book warns that a person appearing in public in a fancy carriage may attract robbers, it means Don’t leave your Aston Martin unlocked. Or, more generally, Beware of the danger of arousing envy.

The I Ching presents a coherent, systematic world view and philosophy, grounded in assumptions that may be very different from yours. Very often, it leads to conclusions different from those that Westerners ordinarily might reach. Over time, readers of this book find themselves cultivating a more subtle way of thinking, a heightened awareness of the myriad possibilities in any given situation. It will influence both your strategy and your tactics. Sometimes, the best way to advance may be to do nothing at all.

Because this way of thinking is so profoundly and completely alien to so many people on the far side of the East/West cultural divide, it can powerfully challenge what we take for granted. For a leader who wants to learn, understand, and grow – a real leader – such challenge is precious. By immersing us in a fundamentally different perspective – yet one that is self-evidently valid and credible – the book enables us to see our own world with fresh eyes.

This text is designed to be read in short sections – essentially two pages each. The book is composed of 64 sections, all organized and formatted in exactly the same way. Once you get used to the I Ching’s brilliant, random-access design – and its admittedly peculiar modes of thought and expression – it becomes incredibly easy to find the two-page section most pertinent to you right now, and to absorb it in minutes. Later on, you can reflect on the meaning of what you’ve read at your own convenience, for as little or as long as you like. You can consult the book once a day or once a decade. It’s powerful either way.

Another great thing: the book is written to help people who aspire to be both successful and “superior.” (The original audience was princes and their ministers.) On the one hand, the I Ching is radically pragmatic, rooted in a sophisticated understanding of practical reality. On the other hand, its context is a universe seen as fundamentally coherent, within which certain types of action, certain ways of thinking and being, consistently work better than others. The “superior man” – let’s translate that as “effective leader” – is one who understands how reality works, and behaves in ways that succeed because they are genuinely aligned with the way things actually are.

There is a moral message here: So long as you take your guidance from reality itself, it is both practically and morally superior to go with the flow instead of trying to push boulders uphill. Sometimes it may be necessary to fight to the death; sometimes retreat is best. The I Ching is always flexible, wedded only to this principle: The ability to recognize the needs of the time is the key to effective action. The practical advice, sometimes strategic, sometimes tactical, always relates to the possibility of being in harmony with what is. The I Ching is useful, and it’s deep. It’s about what to do right now, and it’s about all the gigantic questions that humans have pondered for ages – at the same time.

Instead of offering theory or extrapolating from a few success stories, as so many modern leadership tomes do, the I Ching helps you learn to perceive for yourself the single most important thing: what to do now. In this sense, it resembles the better-known Art of War by Sun Tsu. No less a pragmatist than Henry Kissinger, writing in On China, has praised the practical effectiveness of Confucian thought.

At first, for some, the book may just seem strange.

The language of the I Ching starts with a binary code: lines that change, and lines that don’t change. It’s like matter and energy in physics: two different states of the same thing, each of which behaves differently. These changing or unchanging lines are grouped into trigrams composed of three lines: You may have noticed such trigrams in the flag of South Korea. Each of the eight resulting trigrams is associated with a particular image: for instance, three unchanging lines represent Heaven, which represents creative energy. The other trigrams are Earth, Water, Fire, Mountain, Lake, Thunder, and Wind. Each has a rich and complex set of attributes, associations and meanings. Then the trigrams are combined into hexagrams of six lines, giving rise to 64 possibilities, which map to the 64 sections of the I Ching. Unfamiliar all this may be, but the symbolic language of the I Ching is orderly, systematic, and rich in meaning. Fundamentally, it’s quite simple. Once you get the hang of it – and it isn’t that hard – your mind starts to expand.

The two-page sections for each hexagram contain a Judgment and an Image, each just a few lines long. These are concise, poetic definitions of the nature of the present moment, first stated in terms of situation, then in terms of imagery. The good news is that these are accompanied by a few paragraphs of lucid explanation, based on ancient commentaries but translated for Westerners by Westerners. The commentaries make the meanings clear, and collectively, over time, they teach us how to engage successfully with the I Ching.

Once you begin to understand the language, the book becomes useful. You test its guidance. If it works, you persist some more. Gradually, the underlying philosophy becomes apparent, and you may notice that you’re starting to integrate it into your life. After a while, the underlying concepts become fascinating, and you may want to understand them. You go deeper and deeper, gradually noticing that there’s no limit to how deep you can go. For people who want to understand, it’s the perfect book. It’s like having your own on-call guru or sage – but in the form of a book that packs easily in your suitcase.

Many people consult the I Ching as a lifetime practice. It can become a core discipline in your life, like running or yoga or meditation. There’s no end to its value.

Although the I Ching traditionally is attributed to the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551 B.C.E – 479 B.C.E), scholars tell us this body of knowledge accumulated and was codified over the course of centuries. What’s clear is that it’s a product of ancient Chinese culture and is associated with the philosophies of Confucianism and Taoism; I’m no expert on either.

The reader who, like me, arrives knowing little or nothing about these traditions, requires an assimilation process. You have to become accustomed to an alien mindset. It’s like being an American expat in Japan or India: You start to notice that the culture around you, however unfamiliar, has something valuable going on. If you’re smart, you try to absorb it. Takes a while, but the payoff is huge.

The one truly weird thing about the I Ching, from a Western perspective, is that it is conceived as an oracle. In other words: a fortune teller. There’s obviously something mystical in that, and you may not go for it. My advice: Park that very Western thought, and see whether you like this very Eastern book. The esoteric questions can wait. (The good news is that the philosophy in the I Ching does not require any belief. There’s no religion here, in the Western sense of the word.)

The divination process boils down to what we’d call random chance. It’s not unlike those one-page-a-day desk calendars that give you one Dilbert cartoon or whatever per day. As far as you’re concerned, the sequence is random, but it’s not hard to accept the idea that this is today’s Dilbert cartoon. In the old days, the Chinese used a complicated procedure involving yarrow stalks to determine which of the 64 sections contained the immediately pertinent information. Later on, a simpler method based on tossing coins was invented; that’s what I use. These days, the easiest method for beginners is online: go to http://www.cfcl.com/ching/, click a button, and you’ll know instantly which section of the book to read.

As for the philosophy: At its center is the idea of harmony. The idea is that there’s a way to get right with the world, to get aligned with how things are. If you stop fighting it, you conserve energy that can be used to achieve your ends when the moment is right. If you go with it, you get the benefit not only of your own energy and force of will, but the support of much larger forces in the surrounding environment. You become more likely to win. And if you have to change in order to do that, so much the better: The new you will be an improvement.

The I Ching is also known as The Book of Changes. A fundamental principle – a core insight or assumption – is that everything is always changing. If so, then it becomes critically important to understand the state of things right now. Surely there’s a right time to sell your company, and a wrong time; isn’t it obvious that you need to discern the difference? Similarly, there’s an effective way to resolve a disagreement, and ways that might not work quite as well. Should you act forcefully, for instance, or bide your time and listen to others? The answer may depend on exactly who’s in the room, the characteristics of all the interpersonal relationships, and many other factors.

The Western approach might be to try to analyze all these factors – or just to ignore them and allow your temperament to dictate your behavior. By contrast, an Eastern approach might be to develop a gut sense of the essence of the situation, and then use that in the effort to prevail. The I Ching never tells you what to do – that’s your job. The I Ching’s job is to make you more aware of now. This is useful information. Regardless of the specifics, the principle is that if you understand the nature of the present moment, you can exploit its possibilities. If you don’t – well, you’re on your own.

Perhaps none of us should need an oracle. But the fact is that being fully attentive to the possibilities of the present moment is not easy, what with all the incoming pressures, distractions, unexpected difficulties, and too-much-information of daily life. That’s why a wide variety of traditions consider the ability to remain grounded in the present moment an attribute of enlightenment. It ain’t easy!

So it’s kind of handy to have an oracle around. It helps build the habit of pulling yourself out of the crazed momentum every now and again, to experience a moment of quiet contemplation. You start to notice the wisdom in your own thoughts, which may have been crowded out by TMI. You remember who you are, and what you are trying to do. Refreshed, you then go back to doing it – and maybe you do it better.

There’s more wisdom in this book than I can possibly convey. Here, for example, is one passage that has stuck with me over the years. It’s from the 43rd hexagram, titled Break-Through (Resoluteness):

If you brand evil, it thinks of weapons, and if we do it the favor of fighting against it blow for blow, we lose in the end because thus we ourselves get entangled in hatred and passion. Therefore it is important to begin at home, to be on guard in our own persons against the faults we have branded. In this way, finding no opponent, the sharp edges of the weapons of evil become dulled. For the same reason, we should not combat our own faults directly. As long as we wrestle with them, they continue victorious. Finally, the best way to fight evil is to make energetic progress in the good.

As you can see, the language is unusual. But one wonderful thing about this book is that it imposes no definitions upon us: it’s up to us to define what good and evil mean.

The strategy of avoiding confrontation in this passage – the jujutsu move it proposes – may not be the default for most Westerners. To some readers, that may make it interesting and worthy of consideration.

And the moral tone, the assumption that changing the world begins with changing ourselves, may not be what we want to hear. No serious person commits easily to a path of self-mastery. And I’d argue that no serious person can avoid the challenge of self-mastery.

All that is a big part of why the I Ching can be so extraordinarily helpful to leaders, or to anyone who wants to become more adept at life: It helps us view things from a fresh perspective. It expands the range our perceptions. It creates entirely new options. It helps us see around corners.

Give it a try. If you have any questions, let me know.